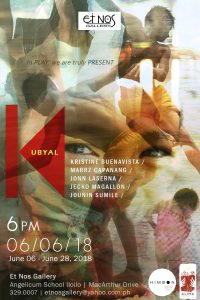

An art exhibition with children’s toys and childhood play as a subject is something that could not be taken lightly. This is what the five artists who mounted “Kubyal” have conveyed during the unveiling of the show at Et Nos Gallery at the Angelicum School Iloilo.

Kubyal presents a multifarious medium with collage, mixed media work, acrylic on canvas, oil on canvas, installations, and mural. The works are interpretations of childhood memories and playtime experiences by artists Kristine Buenavista, Marrz Capanang, Jonn Laserna, Jecko Magallon, and wood sculptor Jounin Sumile.

The toys exhibited at the table were works by Agustin Batiller, a friend by the artists who they fondly call by its nickname Tikô, brought viewers down the memory lane with his Tarak-tarak, Tulutelepono, Pitiw, and Tirador, among other toys popular among children in the past.

The toys at the gallery were not the types that one would have encountered at toy stores at the malls. On the contrary, it showed playthings that were manually assembled from disposed or used materials and put together using human imagination, creativity, and skill. Its outcome were functional toys that are seldom seen these days.

The toys could be considered ‘old school’ yet viewers could easily relate to the art materials. It pierced childhood memory with nostalgia and acclaimed human ingenuity with delight, especially among adults who experienced creating toys from found objects, cans, ropes, and old slippers.

Play enriches imagination and cultivates creativity

The word kubyál reminded viewers of their parents as children. The word kubyál (or also hubyal or húblag) were often heard from mothers when they call upon their children to come home after playing all day at the neighborhood by saying: “tama na nga hubyal, pauli na” or meaning, enough of the frolicking or play and come home now.

Hence, kubyál usually described children who were active and energetic at play and who comes home at dusk sweaty, smelly, and with dust covering their feet. These events, however, underline the integral role of play in the cognitive and emotional development of children.

“Natural, unadulterated play is important for children” shared Jorvelyn Jaruda-Espinosa, “because it could foster their imagination to create something more than the items that they hold as toys.”

Espinosa, who is the founder and director of Maya Play Garden and Daycare Center, demonstrated how the five senses could work together and shape the dynamics of play from their imagination using a stick, a cloth, and a ring as toy materials.

no images were found

“Simple materials that are found from our surroundings are beneficial to children,” said Espinosa as she offered distinction of the difference between ‘open-ended’ and ‘closed-ended’ toys.“Closed-ended is the prevailing toys among children these days – gadgets, electronic, and battery operated. This is, however, passive play,” she stressed, while “open-ended toys are any item yet it could stir imagination among children and allow them to expand possibilities; hence, it is active play.”

“Open-ended toys,” she shared, “are interactive and engaging. These are elements that are important for children when playing for they are using a lot of their senses.”

Espinosa reminded viewers of the exhibit that “passive play creates a lot of problems among children: under-developed motor skills, inability to interact or socialize with others, and obesity, among other health problems.”

The healing power of art and play

Two of the artists, Kristine Buenavista and Jounin Sumile, shared how art, play, and interaction with friends have buoyed them out from panic attacks wrought by an anxiety disorder.

The works that they exhibited hinted traces of their struggles against the mental demons that attacked them because of depression. They illustrated how art and play served as a significant trajectory in their lives and how it liberated them from the dark episode.

For Buenavista, her work served as a reminder of the years she spent with her five younger siblings enjoying the play, domestic work, and bonding.

“As the eldest among the children, I cared for my younger siblings and we have shared a lot of kubyal moments,” she expressed, and “mind you those playful moments sustained me during my period of struggle against anxiety disorder.”

“It was the child in me that allowed me to thrive and survive,” Buenavista recalled with relief.

no images were found

Jounin Sumile, on the other hand, shared that his works served as a footnote on how anxiety gripped his life to a halt after it manifested through severe panic attacks. “I was literally confined at home for close to 3 years and it was my friends and passion for art that facilitated my healing from the disorder,” he recalled.“I stopped art making when I reached high school for I have to attend to new priorities,” intoned Sumile, “but it was my friends from the art community who encouraged me to go back to art making.”

Honed by competitions that he has joined since a young elementary student, Sumile has excelled in art and he is a recognized wood sculptor. The healing power of art and play allowed Sumile to regain control of his life and sooner reclaimed his command on his art.

Childhood play influencing art

Bringing up the childlike spirit to the exhibit is Jecko Magallon. His collage and mural work typified playfulness exemplified by bright shades to highlight characters and vibrant hues to render joyous shapes.

“My work is about the play and I am fond of on-the-spot painting because it is moving, messy, and I like the idea of a work in progress,” said Magallon.

“My mother believed that I have ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder) as a boy, but I later found out that my character is similar to what “indigo children” are described.

Indigo children are children who have special and unusual abilities, if not supernatural.

Moreover, sharing a strong connection to childhood play, Jonn Laserna’s work showed memory of collective play during fiesta season at the community. “These events bring a lot of playmates to the community and the experience is something that you carry later on even when you play alone by your lonesome,” said Laserna.

“My work imparts a character of a child,” explained Laserna, and “it is demonstrated my childhood wherein I wake up in the morning and I go out to play with friends at the neighborhood unmindful of obligations or responsibilities.”

Another artist whose works are usually emblematic of his conscious connection with nature, Marrz Capanang’s installation work Hulurma used sand from the shoreline of the beach where he grew up.

“The sand has a string connection on my childhood and playtime moments for I used it to shape figures like houses and communities with it,” he said.

The concept of Kubyal, Capanang explained, “is grounded from our (the artists) experiences and learnings as children at play. At this age and time, our coming together were simply like playmates where the play is at the center of the activity.”

Kubyal is forthright and straightforward. Its message offers a critical reminder of how children’s play has evolved all these years. It provides a point for reflection on how money has shaped childhood with toys serving more like commodities to show status and economic hierarchy in society and not as objects that can help enrich imagination and creativity.

*The article has appeared at the In The Frame Section of the Iloilo Metropolitan Times in June 2018.